Notes on The Art of Profitability

The Art of Profitability is a tour through the mentorship of an accountant in ho-hum telecom firm as he learns different models for business profitability from his eccentric mentor Zhao. [1]

1. Customer solutions profit¶

The case study compares two companies selling financial information. The better company assigns two workers to embed in the company for several months to learn the customer business entirely.

Invest time and energy in learning all there is to know about your customers. Then use that knowledge to create specific solutions for them. Lose money for a short time. Make money for a long time.

2. Pyramid profit¶

The case study highlights Mattel's pyramid of Barbie dolls. The cheap $10 Barbie dolls form the lower steps and the $200 Barbie dolls adorn the top.

A true pyramid is a system in which the lower-priced products are manufactured and sold with so much efficiency that it's virtually impossible for a competitor to steal market share by underpricing you.

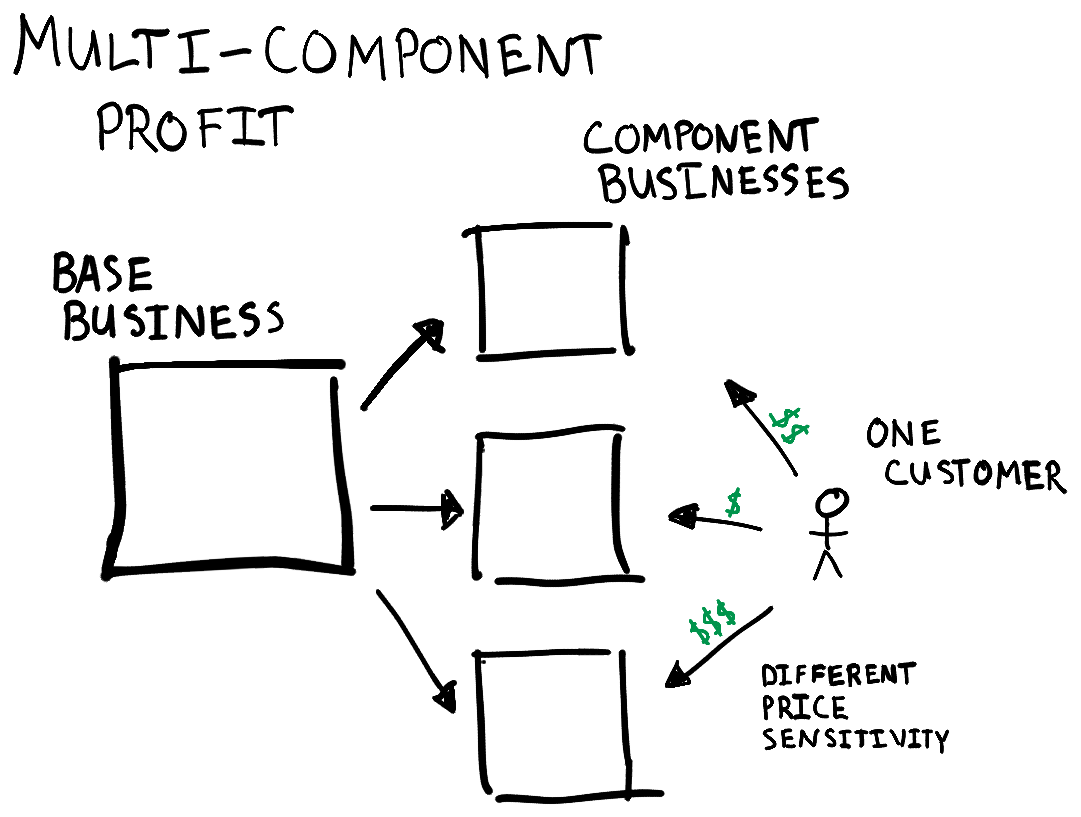

3. Multi-component profit¶

The price sensitivity of a customer depends on their context. A customer at a restaurant is willing to pay 20 cents per ounce of Coke. In a grocery store, the same customer is only willing to pay 2 cents per ounce. Multi-component profit views a business as a series of price-differentiated components with wildly different profitability.

The chapter ends with a warning from Zhao about the telecom business focus on well-made, inexpensive telecom equipment instead of focusing on the first profit model, customer solutions profit: "It's very hard to keep making money, let alone grow, once you've allowed yourself to be boxed into a no-profit zone."

As a real-world example, the CEO of Drop (formerly Massdrop), explains how their largest revenue business component, selling third-party products for a discount. The decision to shut down the third-party sales was especially difficult because all of the key performance indicators were outstanding. The long-term trouble was that the unit economics was awful and the profit margin hadn't improved in the years since introducing the third-party product business component. The CEO, Steve El-Hage, said: "Our long-term value prop for the third-party products was built on price, which is very fragile and fleeting value prop." [2]

Interestingly, El-Hage's analysis matches the fictional mentor's analysis of the flailing telecom company. Zhao warned that "it's remarkable how quickly a structure can crumble once cracks appear in the foundation." Both Zhao and El-Hage warn against competing in low-margin businesses where competition quickly devolves into a race to the bottom. El-Hage instead focused the company on building high-quality boutique products by partnering a vibrant community directly with manufacturers.

4. Switchboard profit¶

The assigned reading for the chapter was Obvious Adams, a short novel by Robert Updegraff published in 1916. The novel is short and an enjoyable read with vibrant metaphors. The main character is a ordinary boy bestowed with a keen sense of obvious solutions and the resolution to accomplish the task. The key point, summarized by the protagonist, Obvious Adams:

Picking out the obvious thing presupposes analysis, and analysis presupposes thinking, and I guess Professor Zueblin is right when he says thinking is the hardest work many people ever have to do.

Our fearless mentor, Zhao, illustrates the switchboard model through the famed Hollywood agent turned Disney President, Michael Ovitz. Ovitz created packages of start actors, screen writers, a directory, and supporting actors and sold them to studios. The genius in Ovitz's play was to add two additional ingredients, First, enrich the package by sourcing compelling stories from literary clubs. Second, represent enough actors to reach a critical mass so that studios need to work with you to get talent. As Ovitz reached critical mass, likely around 15-20%, people perceive the percentage to be much higher which means actors will seek his representation. At critical mass, Ovitz has much greater bargaining power because he represents a significant share of the market and is selling an entire package. Additionally, he can work a higher volume of deals. In total, his revenue per unit time increases 10x.

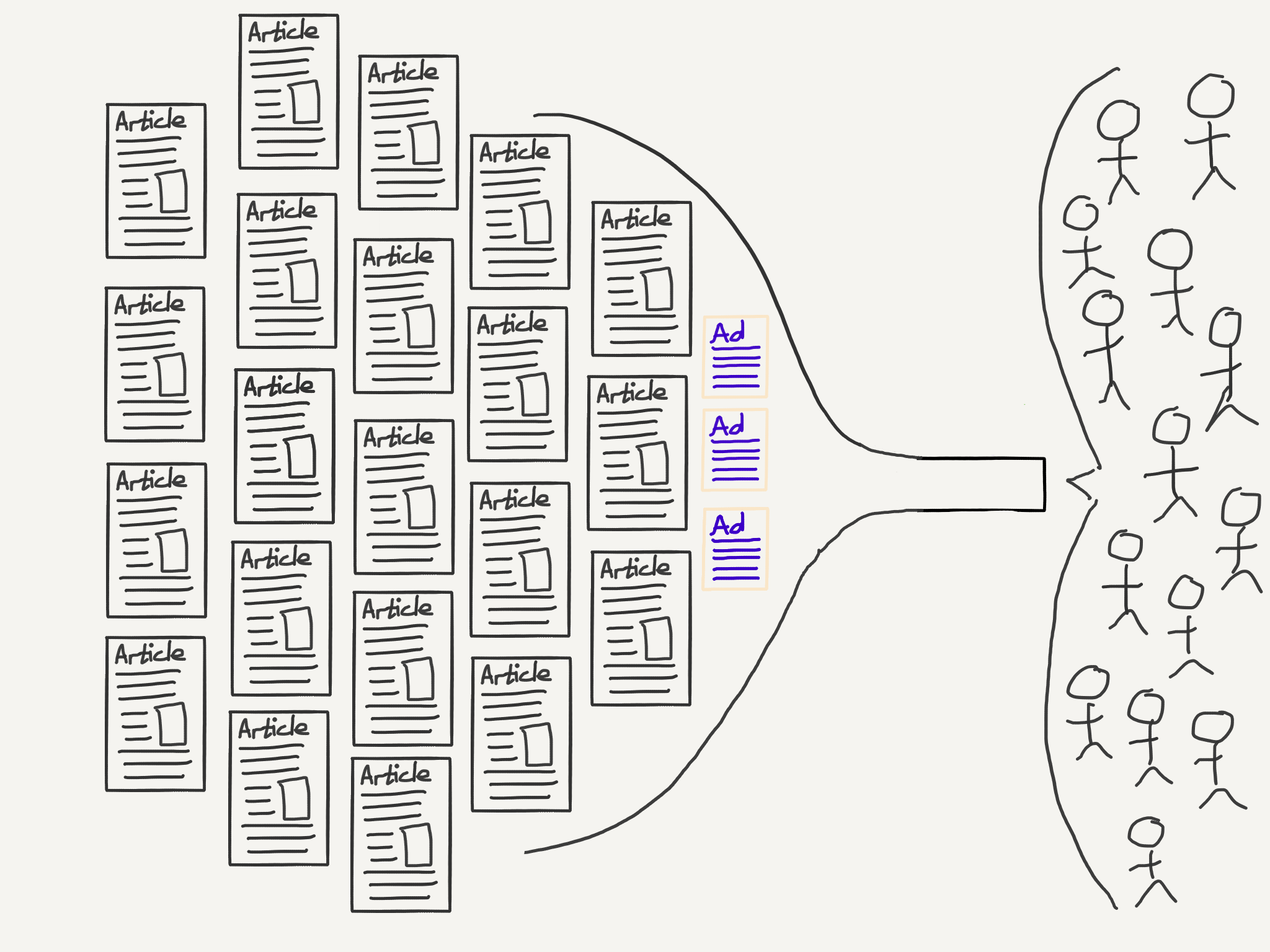

Ben Thompson, of Stratechery fame, classifies this profit mode as an aggregator model. An aggregator attracts "end users by virtue of their inherent usefulness and, over time, leave suppliers no choice but to follow the aggregators' dictates if they wish to reach end users." Since the critical differentiation between aggregators is the number of users on their platform, the platform must be free for users, so advertising is the only available model.